- by Janie Lee

In an article posted by Forbes India on July 10 2013, Dinesh

Narayanan looks at the vocational skilling landscape in India. The article

touches on a few of the issues that pose fundamental challenges to achieving

the ambitious goal of training 500 million youth by 2022. Among these concerns

are on-the-job training, certification, and a lack of meaningful interaction

between stakeholders. Ultimately, Narayanan drives home the point that policy

must be “democratically made and autocratically implemented.”

While both the private and public sectors are grappling with

the right strategy to implement on an autocratic level, individual

organizations are finding degrees of success in placing students and recovering

fees. By sharing best practices and innovative models, all stakeholders can

have more input in determining which strategies could and should be scaled up. Only

then can policy be made democratically.

On a smaller scale, Pratham has had varying levels of

success attempting to create training and placements for youth in India. The

methods below highlight the successful practices that address some of the

concerns that Narayanan has mentioned in his article. We hope to continue an

honest conversation about what is and is not working within the vocational

skilling landscape in India and invite others to do the same.

Strategic

Partnerships

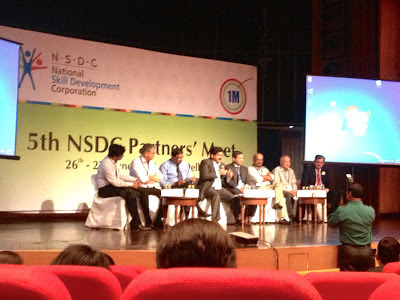

Former labor minister Mallikarjun

Kharge stressed the need for active involvement between the public and private

sectors in order to sure proper and high-quality implementation of programs. Within

each of Pratham’s industry-specific programs, we have partnered with industry

leaders and the National Skills Development Corporation (NSDC). The partners

serve as knowledge partners and support organizations for students from

beginning to end. Partners such as L&T gives us financial support, whereas

others like Taj provide industry exposure through on the job training for one

week. As knowledge partners,

organizations provide oversight during the setup phase of each center, help

develop course content, share assessment tools, provide joint certification,

provide placement linkages, and help audit the center to ensure high-quality delivery

of training.